Among the greatest barriers to broader telehealth adoption are assumptions among policymakers that allowing greater telehealth access will lead to higher utilization and costs. This opinion is especially prevalent for FFS Medicare. Recent data provided to the TTP challenge some of these assumptions.

Among the greatest barriers to broader telehealth adoption are assumptions among policymakers that allowing greater telehealth access will lead to higher utilization and costs. This opinion is especially prevalent for FFS Medicare. Recent data provided to the TTP challenge some of these assumptions.

A small silver lining of the pandemic has been the generation of first-ever Medicare fee-for-service data that allows budget analysts, including the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Office of Management and Budget and the CMS Actuary to begin to assess telehealth’s impact on Medicare more accurately.

Policymakers will, of course, want further analysis of how much COVID-induced care avoidance may have contributed to telehealth’s impact on utilization during the pandemic. However, data generated from provider organizations and the federal government to date show that total healthcare utilization remained steady during telehealth’s expansion and did not substantiate concerns about supply-induced demand.

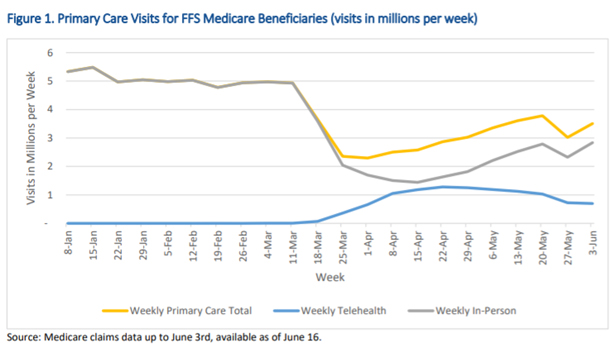

For example, an HHS Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) Medicare FFS telehealth report found that from mid-March through early-July more than 10.1 million traditional Medicare beneficiaries used telehealth.1 That includes nearly 50% of primary care visits conducted via telehealth in April vs. less than 1% before COVID-19.

However, the net number of Medicare FFS primary care in-person and telehealth visits combined remained below pre-pandemic levels. As in-person care began to resume in May, telehealth visits dropped to 30% but there was still no net visit increase. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients seeking or avoiding care still need further analysis, but these data suggest that telehealth substituted for in-person care without increasing utilization.

Other sources mirror ASPE’s findings. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs researchers found that, from March to May 2020, a 56% decline in in-person visits was partly offset by a 2-fold increase in telephone and video visits.2 At least during that period of the pandemic, telehealth replaced in-person visits but did not increase overall utilization.

The TTP obtained initial findings from health systems and independent practices across the country, including Johns Hopkins, Stanford Health Care, Ascension, Intermountain Healthcare, Nemours Children’s Health System, University of Rochester, Northwestern, and Aledade. The TTP also received input from the American Academy of Actuaries’ Telehealth Subcommittee, an advisor to the HHS Secretary, a former Medicare leader and a former Congressional Committee staffer who dealt regularly with the CBO. Using these data, we narrowed our focus to 5 key topics that can impact costs.

- Substitution of in-person care.

- Preventing more costly care.

- Lower no-show rates.

- Greater transitional care management.

- Lowering skilled nursing facilities transfers.

Substitution Effects. It is essential to distinguish between the extent to which telehealth serves as a substitute for in-person care as opposed to an add-on. One study estimates that virtual care could substitute for up to $250 billion of current U.S. healthcare spending,3 and the emerging data from the pandemic shows this could be correct. It is still too soon for large-scale, academically rigorous analysis of what is happening that properly discount pandemic effects, but the evidence from March to July is promising for telehealth.

Data gathered by the TTP indicate that telehealth largely substituted for in-person care and did not increase the total number of visits. Again, policymakers will want further analysis of the separate phenomena of cost related to COVID-induced care avoidance and cost related to widespread access to telehealth. However, as with ASPE, health systems surveyed by the TTP found that telehealth simply represented a change in care delivery modality with steady overall utilization. Total visits, including in-person and video, never went above pre-pandemic levels, even as clinics reopened to in-person care broadly across the health system.

Preventing More Costly Care: Telehealth facilitates access to healthcare for individuals who might otherwise skip or avoid important services. It also allows care delivery more quickly and efficiently in lower cost settings. The TTP found evidence that telehealth can help reduce more costly urgent and emergency department (ED) care, as well as use of costly and often overused services such as imaging.

- Ascension Health found that, from March to May of this year, nearly 70% of patients would have gone to either urgent care or the ED had they not had access to virtual care. These patients would have used more costly options without access to telehealth.4

- Nemours found that 67% of parents who used its 24/7 on-demand virtual care service before COVID-19 reported they otherwise would have visited an ED, urgent-care center or retail health clinic had telehealth not been available.5

- A pre-COVID-19 Anthem study of Medicare Advantage claims data for acute and non-urgent care utilization found savings of 6%, or $242 per episode of care costs by diverting members to telehealth visits who would have otherwise gone to an ED. The study also found less use of imaging, lab tests and antibiotics.6

- In a pre-COVID-19 study of 40,000 Cigna beneficiaries, the 20,000 beneficiaries who used the MDLive telehealth platform had 17% lower costs when compared with non-virtual care. Virtual care users also experienced a 36% net reduction in ED use per 1,000 people compared to non-virtual care users.7

No-Show Rates: Policymakers need to consider telehealth’s impact on no-show rates. Missed appointments decrease care plan compliance which can lead to more expensive care needs. In 2012, CBO determined that prescription drug legislation cost estimates must account for the offsetting effects of medication adherence.8 Telehealth’s similar offsetting effects on no-show rates and better care plan adherence contribute to downstream cost savings and are thus important cost factors. For example, in diabetes care management, routine visits can help prevent long-term costly effects.

“We saw many more farmers getting behavioral health services during COVID that didn’t before. When we talked to them, they were brutally honest, “There’s no way in heck I’m going into a building that says behavioral health, but if I can do it on my iPad at home, I’m okay doing it.” Chris Meyer, Director of Virtual Care, Marshfield Clinic

Health systems and clinician practices consistently report lower no-show rates with telehealth, especially in behavioral care where telehealth removes the stigma of visiting a behavioral clinic. For example, the baseline no-show rate for psychiatry services is between 19 and 22 percent of appointments – while MDLive reports no-show rates of only 4.4-7.26 percent for its behavioral health telehealth visits.9 Dr. E. Ray Dorsey, MD, MBA, professor of neurology and director of the Center for Health and Technology at the University of Rochester Medical Center, commented that patients are more likely to show up to virtual appointments – with no-show rates down about 10% during the pandemic. For the Marshfield Clinic, office visit no-show rates pre-COVID-19 were roughly 5%; they dropped to 3.8% with telehealth during COVID-19.

Improved no-show rates are likely due to telehealth’s convenience, especially its impact on travel burdens that create barriers to care in accessing transportation, taking time off from work and finding childcare. In 2018, CMS estimated that telemedicine saves Medicare patients $60 million on travel, with a projected estimate of $100 million by 2024 and $170 million by 2029.10 CMS also noted that estimates tend to underestimate telemedicine’s impact. Higher projections estimate $540 million in savings by 2029.

Transitional Care Management (TCM): While the TTP did not have time to collect enough data to fully analyze TCM, we received anecdotal evidence that TCM code billing increased during COVID-19. This suggests that clinicians, other providers and patients are more robustly utilizing TCM services. Previous analysis has suggested that increased TCM usage can lower readmissions, thereby reducing health care costs.

TCM service use increased from roughly 300,000 claims during 2013, the first year of TCM services, to nearly 1.3 million claims in 2018. This resulted in significantly lower readmission rates, significantly lower mortality, and significantly decreased health care costs.11 The analysis also found that TCM use is low when accounting for the number of Medicare beneficiaries with eligible discharges. CMS cited this study in its 2020 physician fee schedule rule, noting that increasing medically necessary TCM utilization could positively affect patient outcomes.12 Readmissions are particularly detrimental for patients and hugely costly to providers and payers—in 2019 roughly 83% of hospitals incurred readmission penalties.

Lowering Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNF) Transfers. SNF patient hospital readmissions cost Medicare over $4 billion each year. The TTP received data from Third Eye Health, a platform that triages patients via telehealth who may need to be transferred to the hospital, showing that their consultations between March–July successfully treated patients in SNFs at an overall rate of 91%, including for high-cost falls with injury (84.79%), shortness of breath (66.67%) and acute or chronic pain (95.96%). While much more evidence needs to be collected, the TTP believes telehealth in SNFs may decrease readmissions, as well as hospitalizations and ED visits, yielding significant savings.13

Telehealth and RPM’s impact on reducing strain on the estimated 41 million family caregivers also merits consideration. In 2017, family caregivers furnished $470 billion worth of care, more than total out-of-pocket spending on health care that year ($366 billion) or the total spending for all sources of paid long-term services and supports, including post-acute care in 2016 (also $366 billion).14

Telehealth and RPM also create opportunities for additional communication and information sharing between patients, caregivers and clinicians. Accelerating adoption of value-based payment models, which have shared financial risk to incentivize prevention, chronic disease management and efficiency, can integrate telehealth.

“On the fee-for-service side, the technical fees paid to in-person and telehealth visits should be commensurate with the cost and benefit of providing the service. Otherwise, institutions may favor physical visits over telehealth for reimbursement purposes.” Ricardo Munoz, MD, Chief, Division of Cardiac Critical Care Medicine & Executive Director, Telemedicine, Children’s National Health System

Finally, debate will continue over appropriate telehealth payment amounts, but key principles can help focus these discussions. Telehealth should be seen as neither inherently driving nor reducing costs. Similarly, payers should have flexibility in rates and sites based on different markets and different situations and should retain the ability to innovate with product offerings that reward value-based providers. It is in everyone’s interest to ensure that telehealth services are reimbursed at a rate that reflects the cost of providing these services and the value that they bring as part of the overall care experience. Appropriate reimbursement and access to telehealth services will allow patients to utilize these services where they and their care team feel it is both clinically appropriate and the best possible way of receiving care.

Cost Recommendations

- Telehealth services should be reimbursed based on a thoughtful consideration of the value provided and the cost of delivery—as is done with in-person care. Flexibility on the use and reimbursement of these services is essential to maximizing the benefit to patients and the system at large.

- When analyzing and discussing telehealth costs, policymakers should take a wider view and incorporate costs to patients and family caregivers, clinicians and other providers, and payers. These costs could—and should—include avoided transportation costs, time spent scheduling, preparing for or waiting for a visit, missed work, child/elder care, missed appointments, and technology/infrastructure costs. Although a change in care modality may create new costs, policymakers should not examine these costs without considering “baked in” in-person costs.

“Value-based arrangements with providers and plans at risk create the flexibility to design models that utilize telehealth where and when it can help improve care and outcomes.” Margaret E. O’Kane, President, NCQA - Accurately assessing the true value – including the cost and quality — of telehealth utilization will require that policymakers focus on evidence of its effectiveness and its ability to meaningfully increase access to care, not previously-held assumptions. Data from the current public health emergency are a first look at the effect on Medicare costs of lifting telehealth restrictions and it does not, at this writing, reflect excessive or unnecessary utilization. However, long-term conclusions and policies based on costs and outcomes in Medicare can only be drawn from data derived during the relatively normal conditions that follow the pandemic. Increased behavioral health utilization during the pandemic may provide a good example of meaningful increased access that has potential to improve outcomes and avoid future unnecessary and costly utilization. This will require further investigation.

References

1 Medicare Beneficiary Use of Telehealth Visits: Early Data From the Start of the Covid-19 Pandemic, HHS Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, July 2020

2 Reduced In-Person and Increased Telehealth Outpatient Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Annals of Internal Medicine, August 2020.

3 Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality?, McKinsey and Company, May 2020.

4 Ascension Task Force on Telehealth Policy, March-May 2020.

5 Analysis of a Pediatric Telemedicine Program, Vyas et al, December 2018.

6 Telehealth Eliminates Time and Distance to Save Money, Healthcare Finance, October 2019.

7 At Cigna, Telehealth Reduces Patient Costs and ER Visits, and Boosts Use of Generic Rx, Healthcare IT News, November 2019.

8 Offsetting Effects of Prescription Drug Use on Medicare’s Spending for Medical Services, CBO, November 2012.

9 Research Reveals Reasons Underlying Patient No-shows, ACP Internist, February 2009.

10 Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Policy and Technical Changes to the Medicare Advantage, Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit, Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), Medicaid Fee-for-Service, and Medicaid Managed Care Programs for Years 2020 and 2021, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, November 2018.

11 Changes in Health Care Costs and Mortality Associated With Transitional Care Management Services After a Discharge Among Medicare Beneficiaries, Bindman et al, September 2018.

12 Medicare Program; CY 2020 Revisions to Payment Policies under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Changes to Part B Payment Policies, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, November 2019.

13 Use Of Telemedicine Can Reduce Hospitalizations Of Nursing Home Residents And Generate Savings For Medicare

14 Valuing the Invaluable, AARP, 2019.

- Save

Save your favorite pages and receive notifications whenever they’re updated.

You will be prompted to log in to your NCQA account.

Save your favorite pages and receive notifications whenever they’re updated.

You will be prompted to log in to your NCQA account.

- Email

Share this page with a friend or colleague by Email.

We do not share your information with third parties.

Share this page with a friend or colleague by Email.

We do not share your information with third parties.

- Print

Print this page.

Print this page.